I’m currently neck-deep in code as I push towards launching S2N Navigator this year. As a result, my Spotlights have become a little more reflective and, at times, a little more wordy.

It is strangely easier for me to write like this, as I don’t need to invest the time I typically invest into research ideas. It also gives me an opportunity to vent some of my software development frustration, which I project today on the tension between elegant theory and messy reality.

{{active_subscriber_count}} active subscribers.

S2N Spotlight

Each Layer Provides a Deeper Experience

When I studied finance, we didn’t have computers, backtesting engines, optimisation libraries, or Monte Carlo simulations running quietly in the background. We had financial calculators — the famous Hewlett-Packard models — and a small set of formulas that felt almost sacred: present value, future value, discounting, and compounding.

Those tools trained us to think in a very particular way. They trained us to take a messy journey and reduce it to two points.

For example, Tesla was trading at roughly $10 (split-adjusted) a decade ago. Today it has traded north of $250. Depending on where you anchor the dates, that’s a gain of more than 2,000% — a compound annual growth rate in the mid-30% range.

Clean. Precise. Comforting.

The calculator doesn’t show you the lived experience between those two points. It doesn’t show you the 60–80% drawdowns. It doesn’t show you the long stretches where Tesla went nowhere while volatility slowly crushed conviction. It doesn’t show you the earnings gaps, the regulatory scares, or the periods where even committed shareholders questioned whether they were delusional. It doesn’t show you the Elon show.

It simply connects Point A to Point B and calls it “the return”.

That habit — compressing lived experience into a smooth continuous story — is the conditioning I want to focus on today. Computers didn’t create it. Computers just industrialised it. And that conditioning quietly shapes how we make decisions.

The seduction of elegant answers

When we look at Tesla in hindsight, a natural question arises: How much should I have invested?

Modern finance offers an elegant answer. We take Tesla’s historical returns, estimate an average return and volatility, and apply a continuous optimisation framework—often some variant of the Kelly criterion—to determine the “optimal” exposure.

In simple terms, the Kelly framework asks how aggressively one should bet to maximise long-term compounding. It is so much more than that; in fact, the name of this publication, Signal 2 Noise, comes from the signal-to-noise ratio that John Larry Kelly Jr developed in his discovery of the information ratio and how it could be used in long-distance telephone conversations.

On paper, Tesla looks compelling. Strong average returns relative to volatility. Positive expectancy. The mathematics suggest that higher exposure — even leverage — would have produced spectacular outcomes. Ex post, excuse the academic flex, that conclusion is hard to argue with. But this is where elegance quietly becomes dangerous.

What the averages quietly remove

The problem isn’t the mathematics. It’s what the mathematics silently assumes.

When we collapse ten years of Tesla’s history into a handful of averages, we aren’t just simplifying; we are removing information that no investor could have ignored in real time.

Those averages treat long losing streaks the same as long winning streaks. They treat deep drawdowns as statistical noise rather than lived stress. Even when we add sophistication — jumps, fat tails, better distributions — the logic remains the same: the path is summarised away. But in markets, the path is the information.

Living through Tesla was not a smooth compounding experience. It was a sequence of belief tests. Confidence was earned, lost, and re-earned multiple times. Any realistic investor’s conviction — and therefore position size — would have evolved along the way.

Continuous frameworks quietly assume it didn’t. They imagine an investor who held the same belief, the same confidence, and the same exposure through every regime — as if uncertainty itself were irrelevant.

That isn’t foresight. It’s hindsight dressed up as precision.

Bitcoin and the danger of compressed belief

We are watching this same conditioning play out in real time with Bitcoin.

The dominant narrative is built on compression. Fixed supply. Inevitable adoption. Therefore, a precise future price — $250k, $500k, $1m — five or ten years from now.

It sounds analytical. It feels disciplined. It makes me want to be sick. What’s missing from these projections is time lived forward. Years where nothing happens. Years where conviction is punished. Years where opportunity cost quietly compounds against you.

After the dot-com bubble burst in 2000, the Nasdaq took roughly 15 years to recover in real terms. That wasn’t a failure of technology. It was a failure of timing, sizing, and certainty. Most people don’t remember that period because they compress the chart. They start in 2003. Or they draw a straight line from the 1990s to today and call it inevitability.

Bitcoin believers are making the same mistake — just earlier in the story.

Scarcity is not a schedule. Adoption is not a straight line. And markets do not reward conviction that arrives before its time. None of this invalidates the long-term case for Bitcoin. It challenges the idea that belief alone is a risk-management strategy.

Discrete thinking isn’t old-fashioned — it’s honest

There is a messier, more honest way to approach this problem.

Instead of asking, “Given the full history, how much exposure would have been optimal?”, we ask a harder question:

“Given what I know right now, how much confidence have I actually earned?”

This is the spirit of discrete, adaptive approaches. Position size evolves. Losses reduce exposure. Extended drawdowns force humility. Periods of stability and confirmation allow size to increase not because a formula says so, but because reality has earned it.

It lacks the soothing comfort of a single optimal answer. And that’s precisely why it works. If I am making you feel uncomfortable, that is good. Embrace it.

I am often quite good at criticising, without providing constructive ways to relook at things. So today I am not going to just expose the problem and leave you hanging; I am going to provide a framework to rethink the way to think.

A practical way to go about it

Start smaller than feels necessary. Early conviction is cheap. Survival is not.

Let exposure earn its way up. Increase size only after the asset survives multiple stress periods under your framework.

Penalise drawdowns mechanically. Large or clustered losses should automatically reduce exposure, regardless of how compelling the narrative remains.

Treat “optimal” allocations as diagnostics, not commands. They describe the past; they do not dictate the future.

Design for survival, not vindication. The market does not care if you’re right eventually. It cares whether you’re solvent in the meantime.

This approach won’t produce the prettiest charts. It won’t deliver clean one-line answers. But it aligns with how uncertainty actually unfolds. The most expensive mistakes in markets rarely come from being wrong. They come from pretending we were ever certain.

Elegant summaries feel safe. Adaptive systems make money.

S2N Observations

Speak of the devil. Bitcoin is currently having a crisis of confidence.

A few hours ago Bitcoin surged +$3,000 in 1 hour and reclaimed $90,000 as $120 million worth of leveraged shorts were liquidated. Minutes later, $200 million worth of leveraged longs were liquidated, with Bitcoin now down to $86,000.

These leveraged traders clearly didn’t study Kelly.

As I am walking around like a bear with a sore head, I thought I would stick my boot into the drunken sailor, inebriated by his messiah complex.

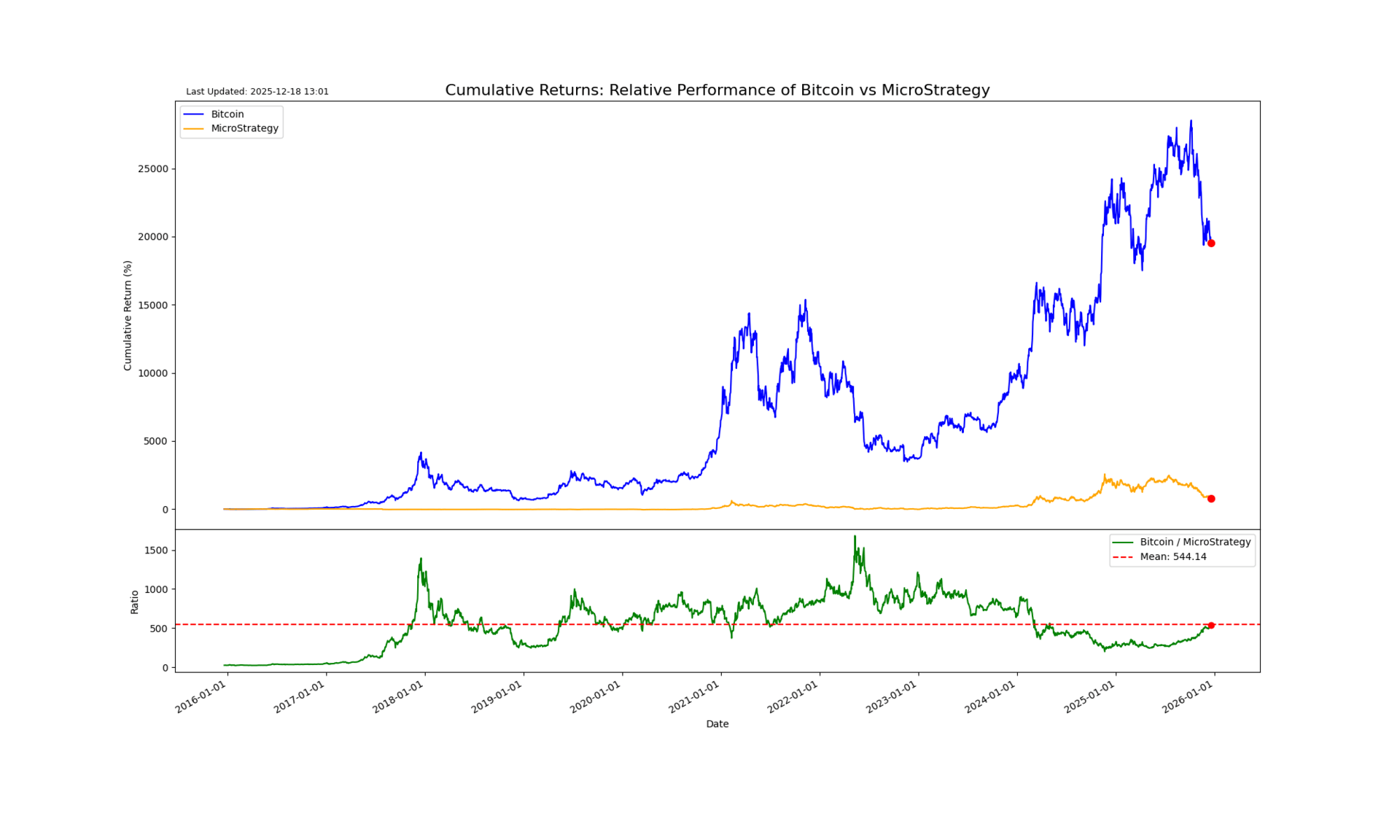

On 14 December, 2025, Michael Saylor through MicroStrategy bought 10,645 Bitcoin for $980 million at an average price of $92,098. This guy loses money quicker than I can say boohoo.

I want to revisit my trade recommendation, short MicroStrategy (I say the old name on purpose out of spite 😎) and long Bitcoin. I mentioned a month or so ago that Jim Chanos was closing his trade out too soon; there was more juice left in the trade. So far he has been right. I am not one to ride a wave all the way onto the sand, but this is one I hope to ride all the way. Let’s hope it’s not rocks – yikes.

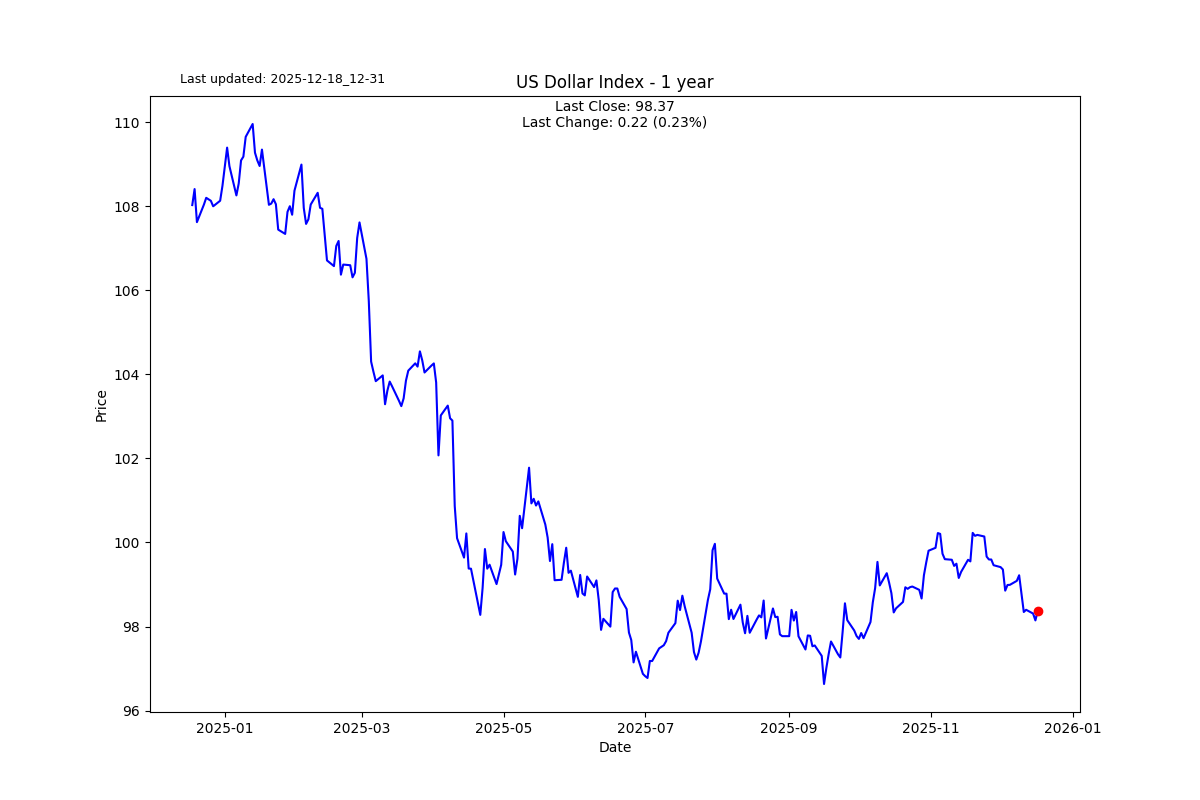

Don’t take your eye off the liquidity stress in the system; Monday was another big day of begging at the Fed’s emergency window ($5 billion). Just like a stress fracture is typically the result of repeated stress, one has to wonder what is going to break with all the stress in the system.

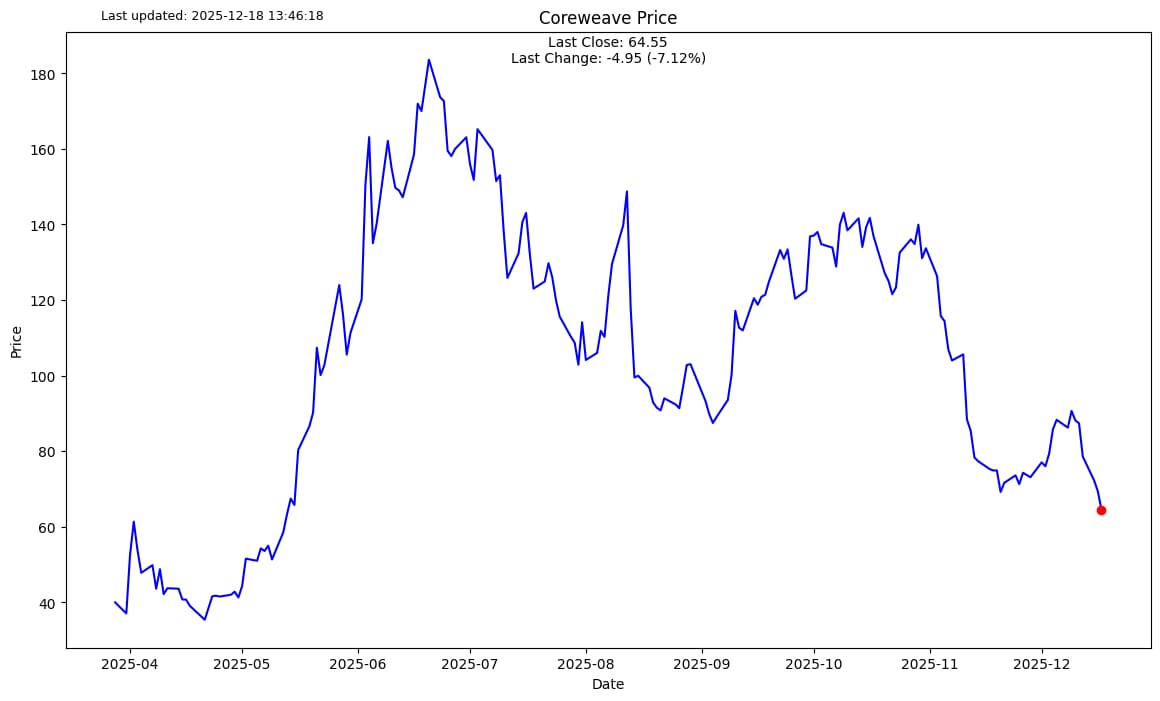

I have mentioned that I am glued to Oracle and Coreweave as my early warning signs that the AI bubble is deflating. Boy, these stocks are being slaughtered worse than a turkey on Thanksgiving.

Anecdotally, I cannot help but notice the inflation creeping into my AI use. Yes, the AI power we have been given as retail consumers is dirt cheap. At the current rate these companies will all be bankrupt in a year or two. I am not making it up OpenAI loses billions every month and has about a year's runway in the bank. So prices have to go up, and when you add the cost of the data centres being developed for these compute hungry machines prices will have to go up dramatically.

My other hard science experience was I bought a chocolate croissant this morning. A little guilty pleasure. I was shocked $6.50 for a pastry that never touched sides.

S2N Screener Alert

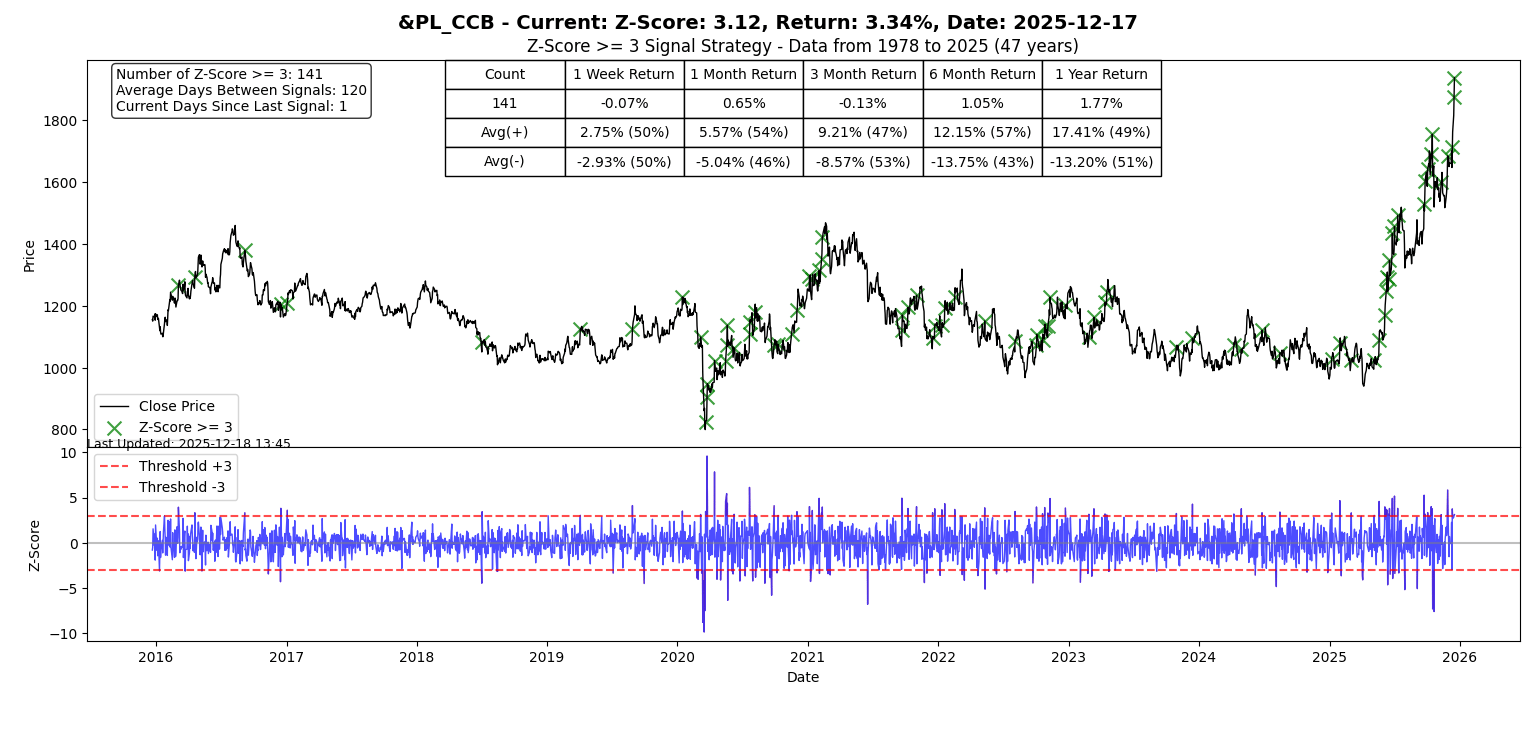

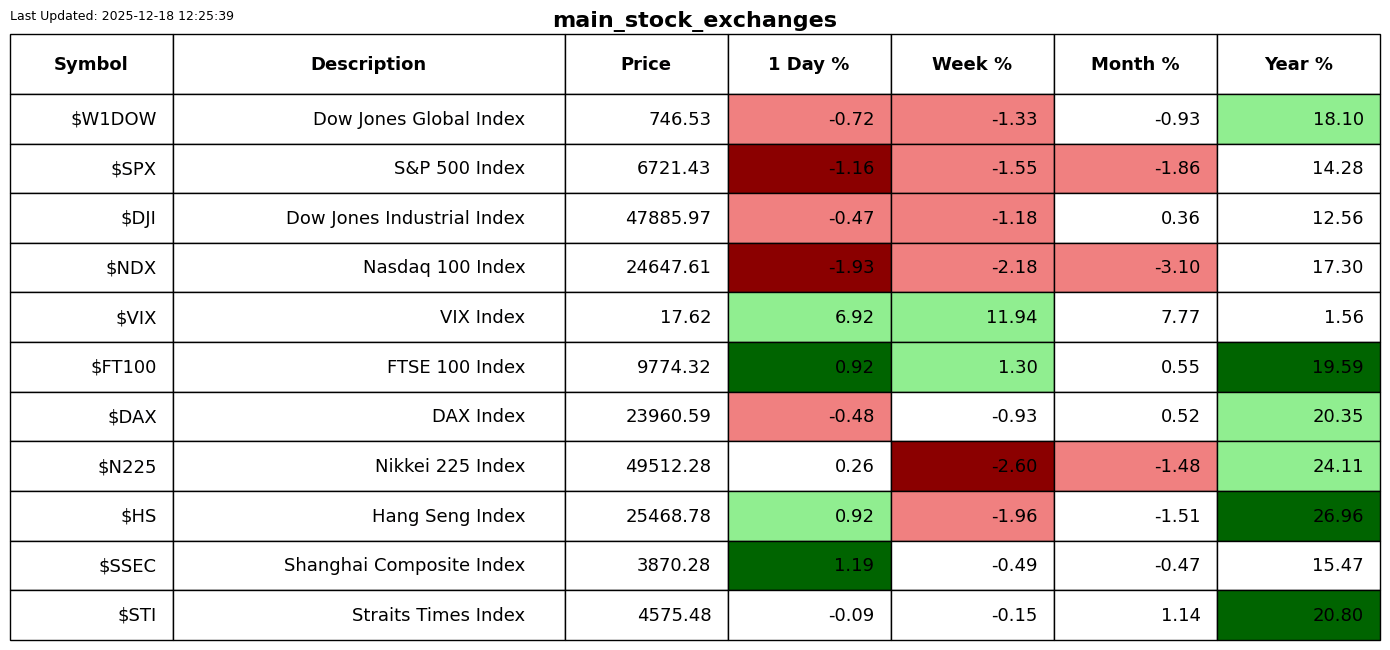

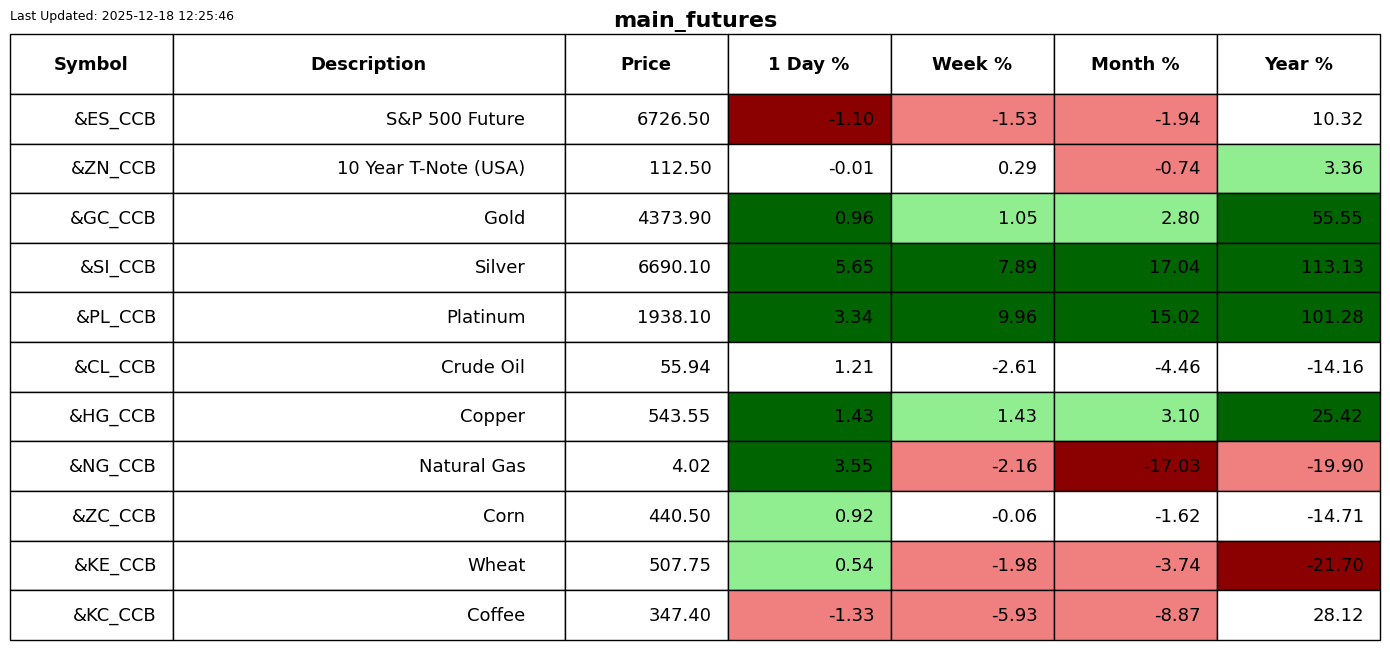

Silver keeps shining bright. A massive 5 sigma up day.

Platinum and Natural Gas also had big days in different directions.

If someone forwarded you this email, you can subscribe for free.

Please forward it to friends if you think they will enjoy it. Thank you.

S2N Performance Review

S2N Chart Gallery

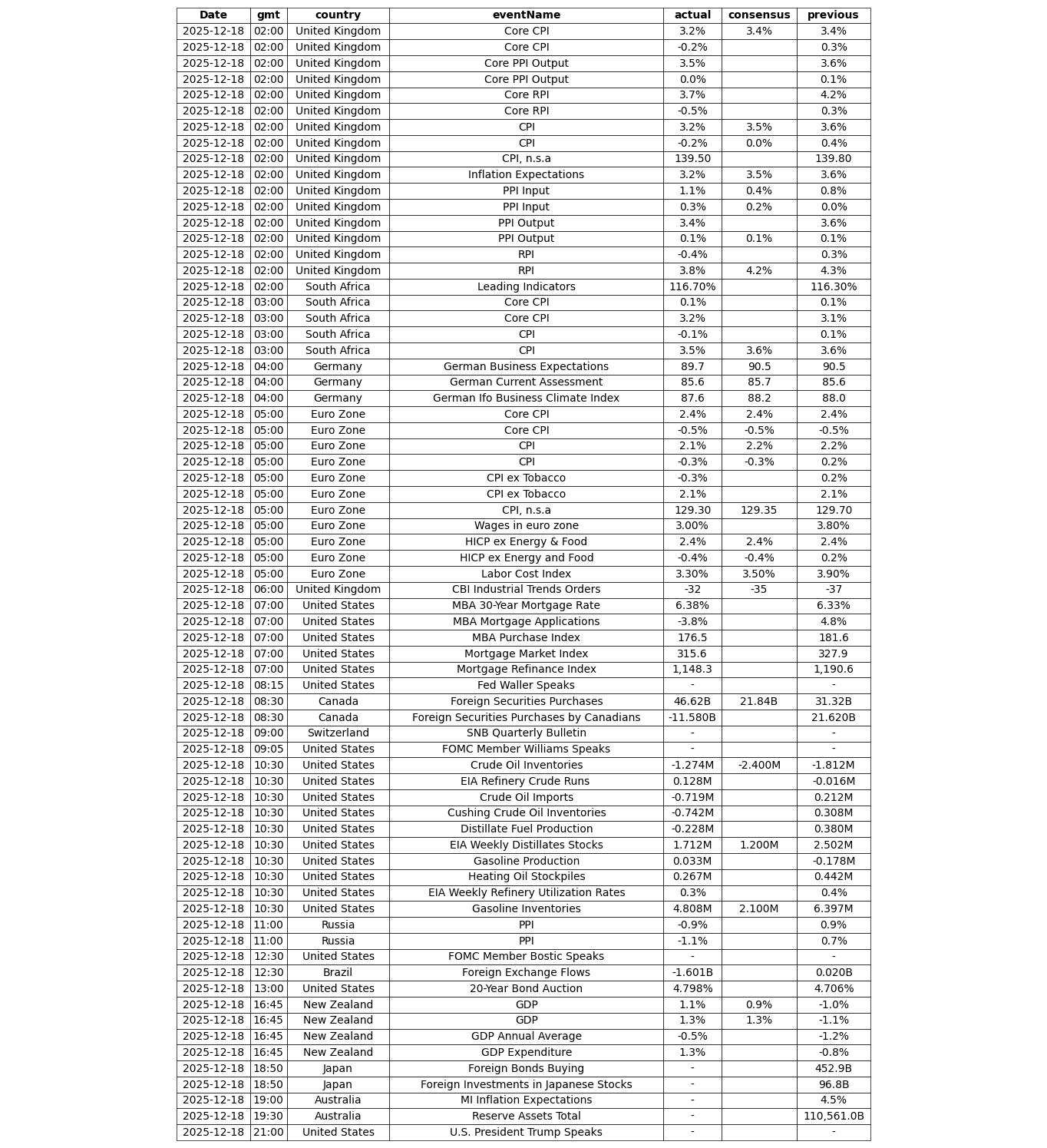

S2N News Today