{{active_subscriber_count}} active subscribers.

S2N Spotlight

As I work towards the launch of my new software business, I am living through the tedious process of compiling.

Anyone who has built software knows this phase well. The work is slow, repetitive, and deeply unglamorous. Nothing new is being created. No breakthroughs. No visible progress. Just a long sequence of checks, clean-ups, dependencies, and confirmations — all in service of something that, once finished, will appear deceptively simple.

I launched a small alpha test group last week and have been working round the clock testing, fixing, and compiling. The process has prompted a broader reflection — not about software, but about how systems compress complexity and how the human mind does something remarkably similar.

Join me on this journey into the thoughts of my makeshift mortuary of a mind; you may actually learn something you never knew before.

The illusion of time speeding up

From when I was a little boy, I was always intrigued by the perception of time and how certain times felt longer than others. There’s a popular explanation for why time appears to accelerate as we age. When you’re five, a year represents 20% of your life. When you’re fifty, it’s only 2%. The mathematics is neat and intuitive — but it is mostly wrong.

That explanation assumes the brain experiences time as a linear accumulator. It doesn’t.

What actually changes with age is not time itself, but how densely memory is encoded.

Neuroscience has shown that the brain is fundamentally an efficiency machine. In early life, when everything is novel, the brain records extensively. Experiences are rich, varied, and unpredictable. Memory density is high. Time feels expansive in hindsight because there is so much stored information to reconstruct it from.

As we age, the brain shifts into predictive mode. It stops recording what it expects to happen. Only deviations from expectation — surprises, anomalies, novelty — trigger deep encoding. This phenomenon is often referred to as the oddball effect. In plain terms: the brain only hits “record” when something breaks the pattern.

The consequence is subtle but profound. Live the same week repeatedly, and your mind doesn’t store ten years of experience—it compresses them into a single memory labelled “routine”.

Time doesn’t speed up. It gets compiled.

Compression is not lossless

This is where the analogy becomes interesting.

When software is compiled, thousands of lines of human-readable code are compressed into something efficient and executable. The output works — but the process that produced it is no longer visible. Complexity is hidden. Friction disappears.

The human mind does the same.

Years of stable conditions — predictable outcomes, familiar patterns — are compressed into a narrow psychological footprint. Only the anomalies survive recall. I am not going to mention examples like the dot-com bubble or the global financial crisis or the Covid pandemic, as you were already identifying the periods in your life that stood out from the ordinary.

This mechanism is not a flaw. It is how cognition scales. But it has consequences. Especially in markets.

When success becomes invisible

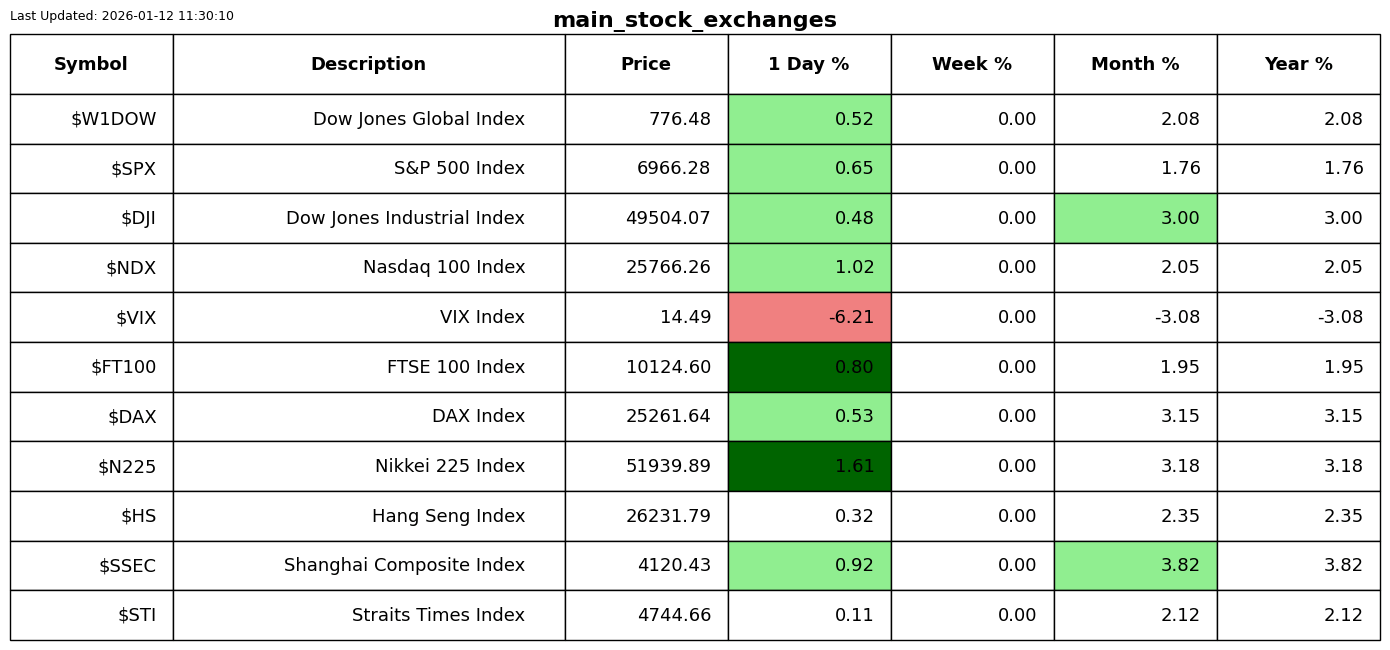

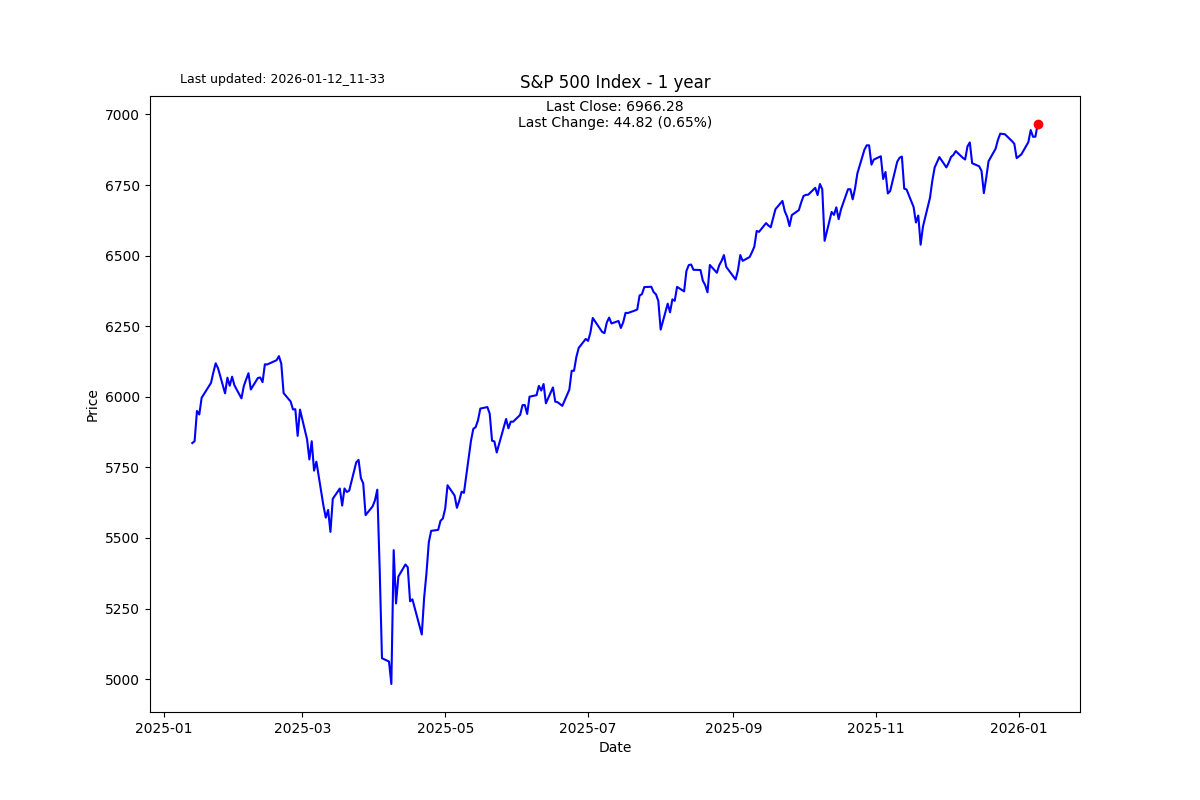

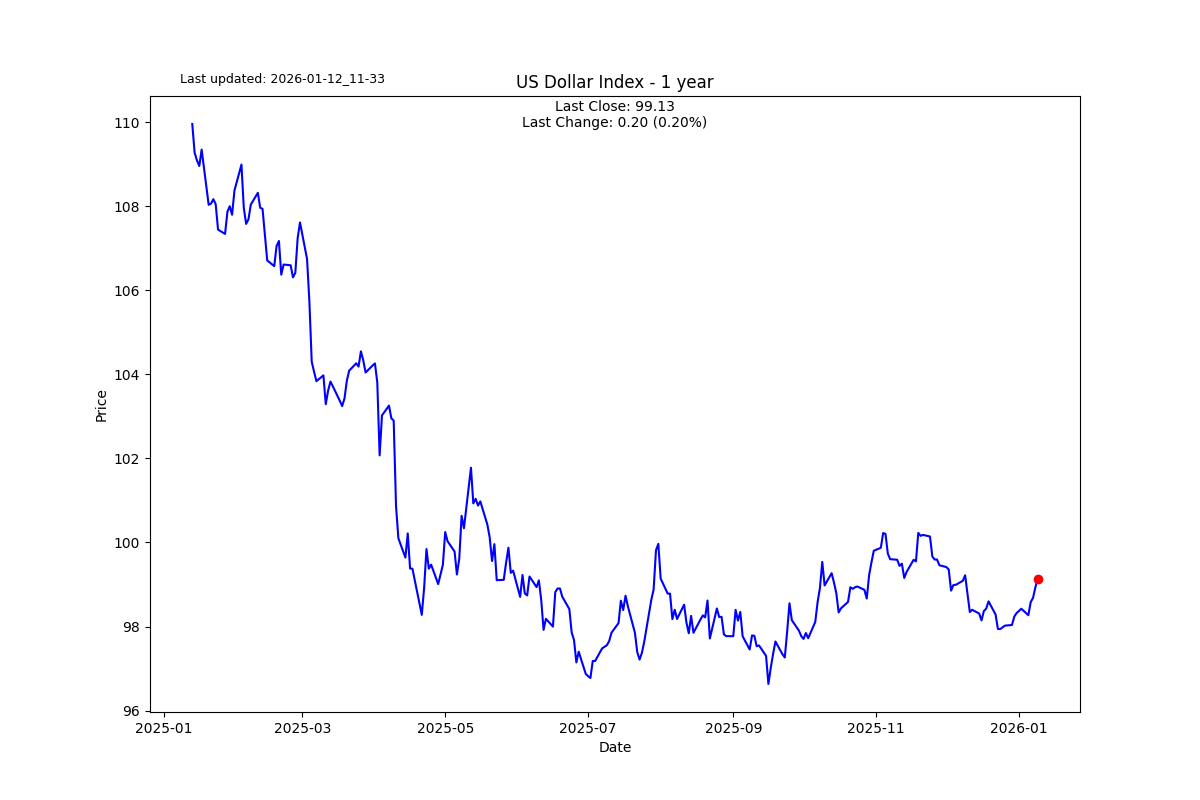

We are coming off an extended period of above-average equity performance.

Strong returns. Fast recoveries. Long stretches where risk was rewarded and patience appeared unnecessary. Over time, these conditions stopped feeling exceptional. They were quietly absorbed into our definition of normal.

And this is where investors get into trouble.

Not because markets inevitably revert to the mean — that’s well understood.

But because expectations revert much more slowly than reality.

Extended success doesn’t just build wealth. It resets baselines.

Average outcomes begin to feel like underperformance. Volatility starts to feel abnormal. Risk controls feel conservative. The extraordinary is no longer recognised as such because confirmatory repetition has compressed it into the background. The anomaly disappears.

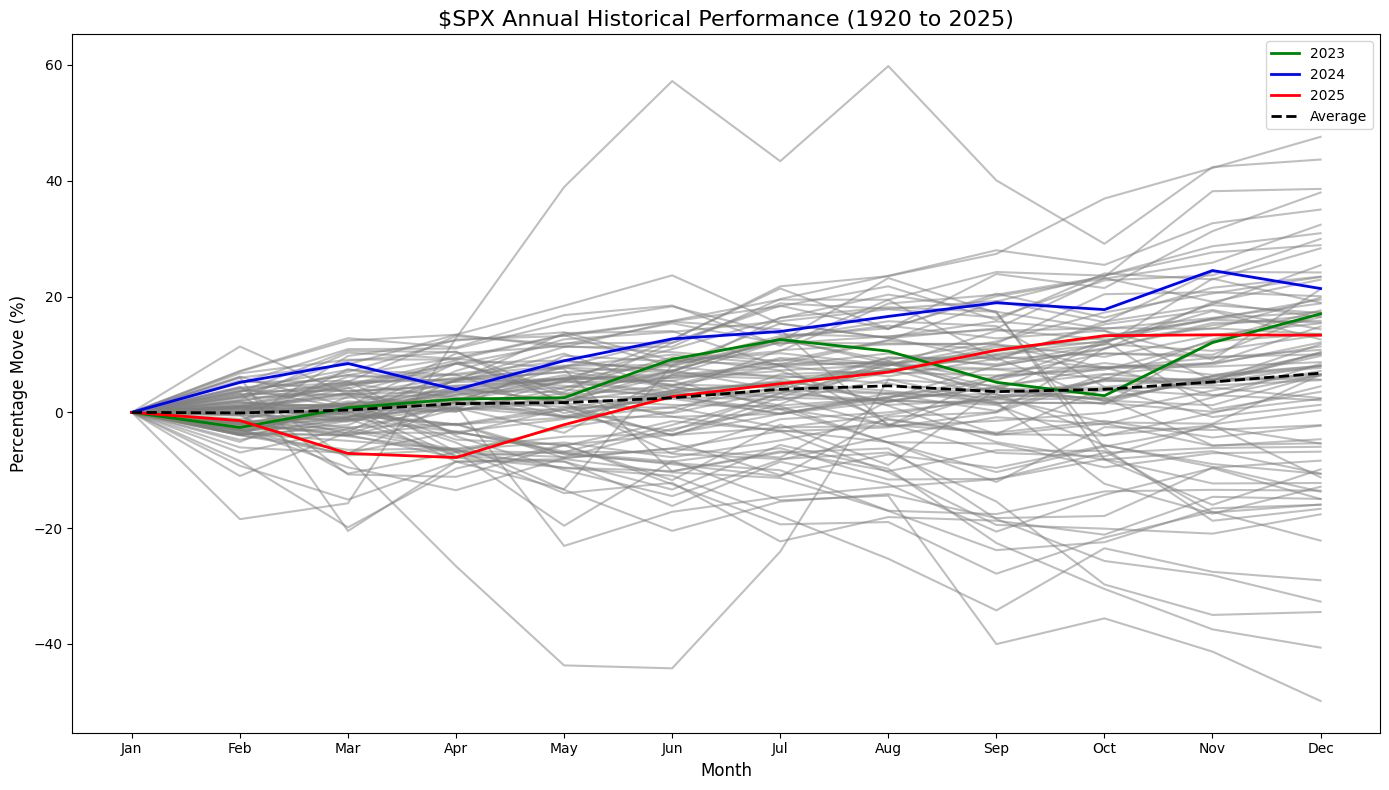

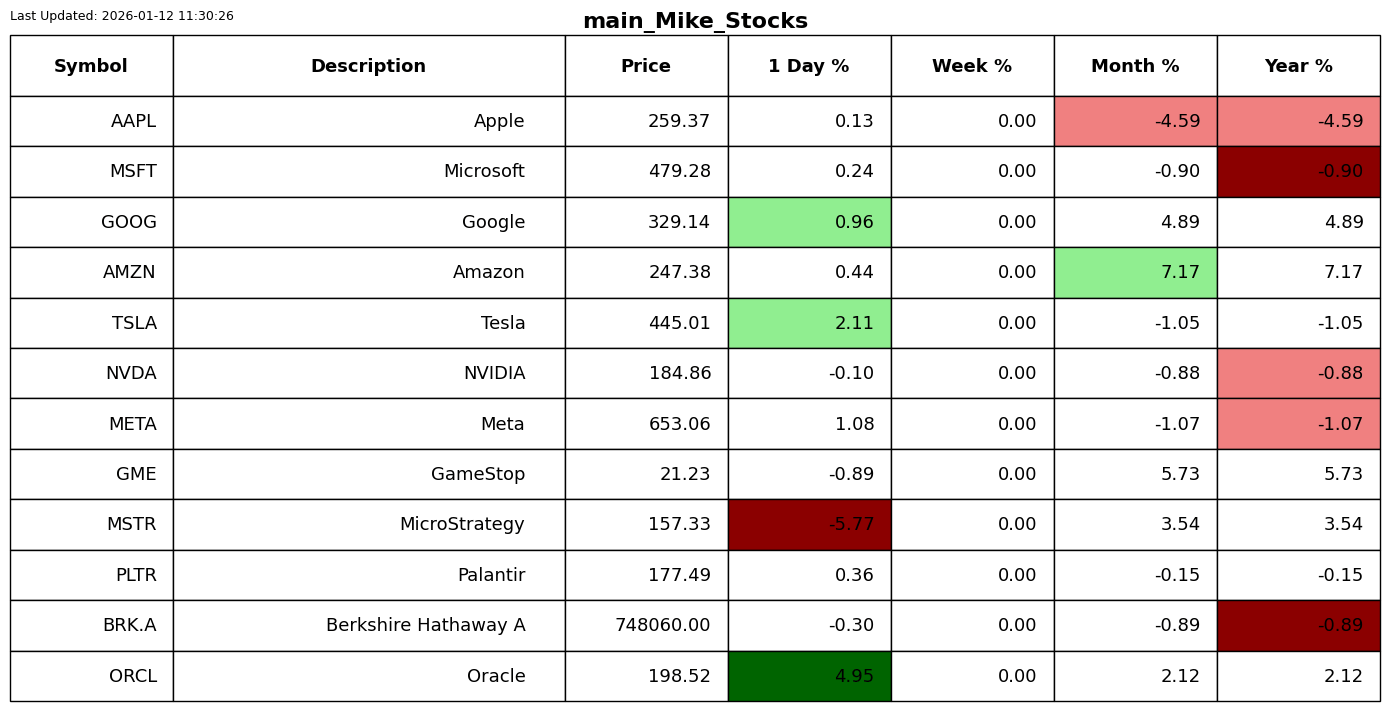

I have created strips of the annual returns of the S&P 500 from 1920 to present. I highlight the last 3 years, which you can see have produced returns well above the 100-year average (black dotted line).

The danger isn’t the downturn

Most investors think risk arrives with losses. It doesn’t. Risk accumulates quietly during periods of success — when exceptional conditions are mistaken for permanent ones and when systems are judged against conditions they were never designed to sustain indefinitely.

By the time markets return to average, investors are not shocked by losses. They are shocked by normality. Let that sink in for a bit. This is not a failure of financial mathematics. It is a failure of memory calibration.

Why this matters now

At the start of a new year, the temptation is always to look forward — new forecasts, new themes, new narratives. I am so sick and tired of people in the newsletter space treating this period as if the market actually cares about New Year’s like I care about staying up for the Sydney Harbour Bridge fireworks.

On the contrary, they don’t call me a contrarian for nothing; this piece is deliberately backwards-looking. It is meant to serve as an anchor for sensibility.

A reminder that:

Average is not failure

Stability is not guaranteed

And extended success carries hidden risks — not just in valuation models, but in expectations

Compounding is built in environments that feel boring while they’re happening. The danger arises when boredom from getting rich is misdiagnosed as expected.

Back to compiling

Compiling software is slow because it is unforgiving. Every dependency must be explicit. Every assumption checked. Nothing is waved through because it “worked last time”.

This year, I’m choosing to start in compile mode. Not to optimise for excitement, but for resilience. Not to extrapolate from the recent past, but to re-anchor expectations to something more durable. Because the most dangerous phase in any system isn’t when it breaks; it’s when it quietly convinces you that exceptional is normal.

S2N Observations

My launch date is fast approaching. I’m not sharing it yet — not out of secrecy, but because real work sometimes needs room to fail quietly.

I am observing the markets extremely closely and thoughtfully. I have tonnes more to share, but for now my brain is overloaded, and I just don’t have the headspace to present thoughtful quantitative and economic research, so you will be left to my philosophical and psychological thoughts for a little while longer as I try and purge my mind from the strings of code torturing my bandwidth.

S2N Screener Alert

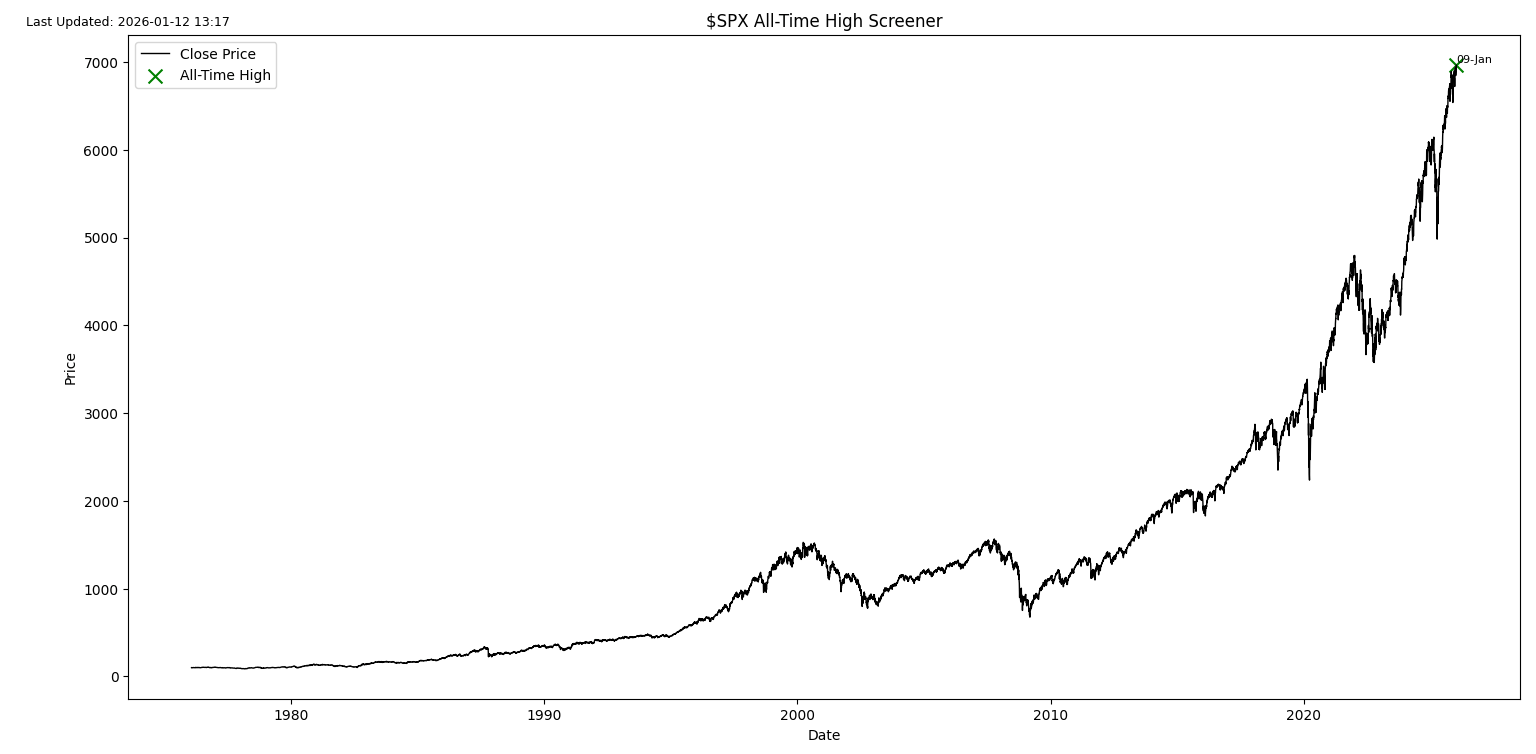

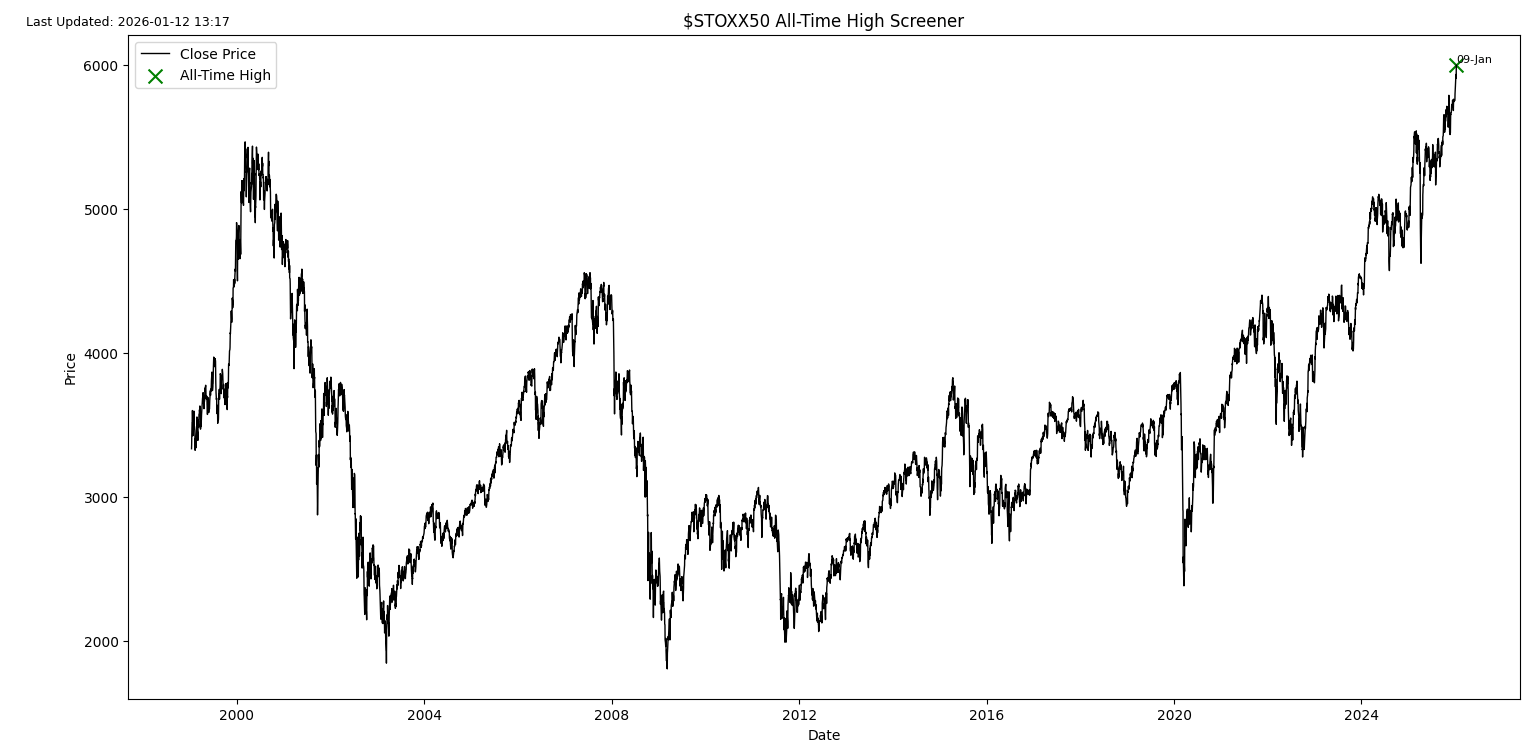

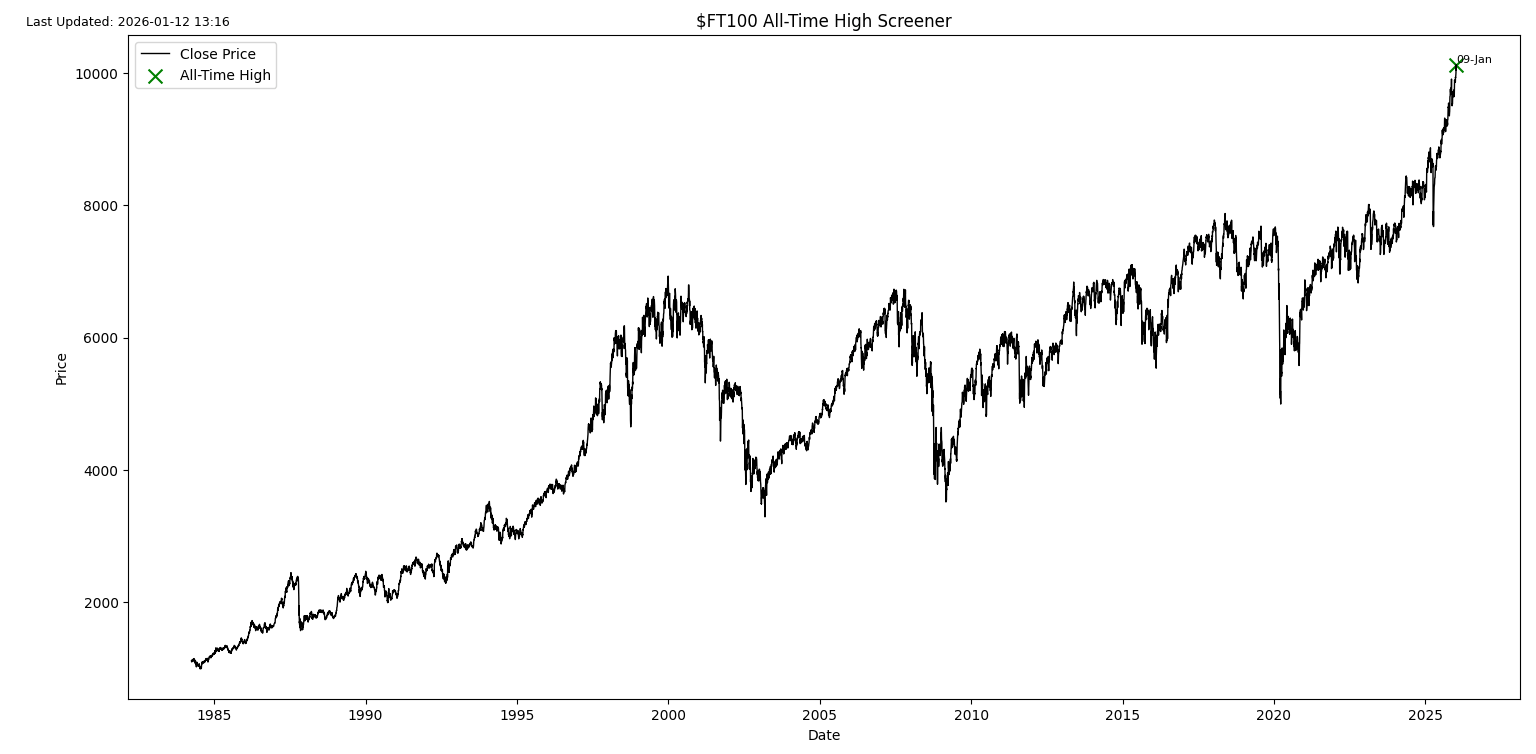

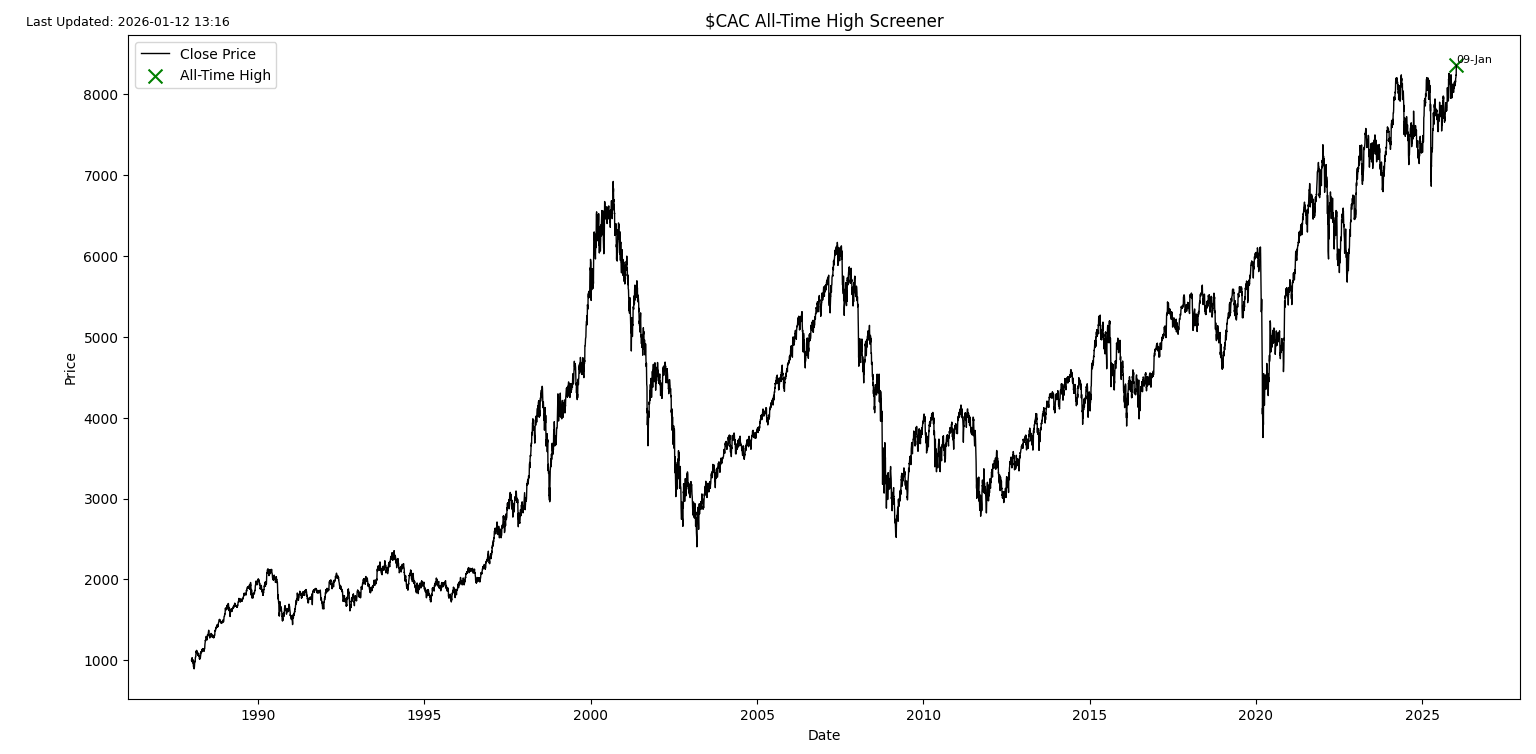

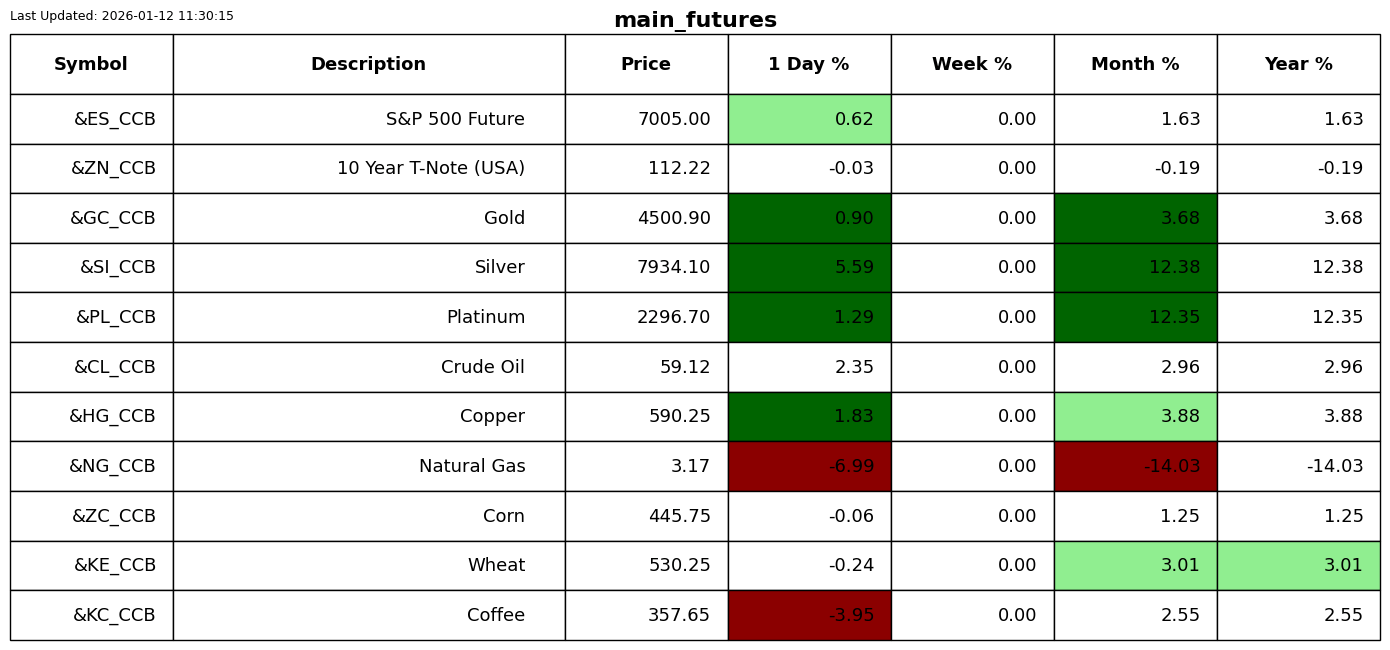

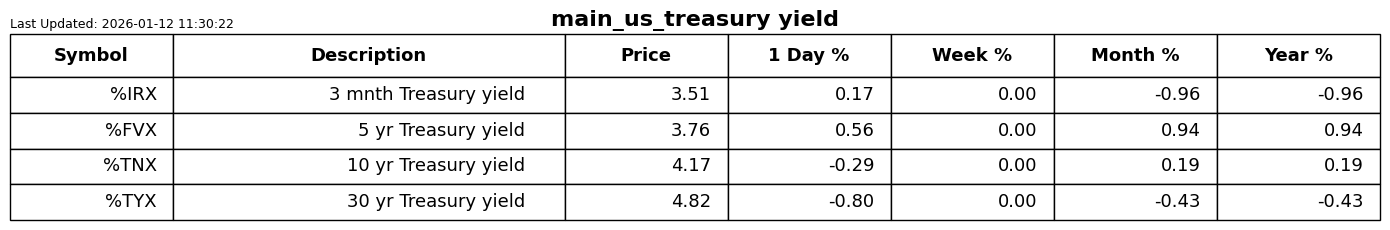

The next few charts illustrate how repetition compresses perception. When new all-time highs become frequent, they stop feeling exceptional. Success turns into background noise. It reminds me of Trump on the campaign trail when he said, 'We will win so much that you will get bored of winning.’

If someone forwarded you this email, you can subscribe for free.

Please forward it to friends if you think they will enjoy it. Thank you.

S2N Performance Review

S2N Chart Gallery

S2N News Today