{{active_subscriber_count}} active subscribers.

Brought to you by Today’s Sponsor

Here’s an un-boring way to invest that billionaires have quietly leveraged for decades

If you have enough money that you think about buckets for your capital…

Ever invest in something you know will have low returns—just for the sake of diversifying?

CDs… Bonds… REITs… :(

Sure, these “boring” investments have some merits. But you probably overlooked one historically exclusive asset class:

It’s been famously leveraged by billionaires like Bezos and Gates, but just never been widely accessible until now.

It outpaced the S&P 500 (!) overall WITH low correlation to stocks, 1995 to 2025.*

It’s not private equity or real estate. Surprisingly, it’s postwar and contemporary art.

And since 2019, over 70,000 people have started investing in SHARES of artworks featuring legends like Banksy, Basquiat, and Picasso through a platform called Masterworks.

23 exits to date

$1,245,000,000+ invested

Annualized net returns like 17.6%, 17.8%, and 21.5%

My subscribers can SKIP their waitlist and invest in blue-chip art.

Investing involves risk. Past performance not indicative of future returns. Reg A disclosures at masterworks.com/cd

S2N Spotlight

I have been reading so many pieces about the AI revolution and its impact on jobs and the economy in general. I have also been engaged in many discussions with people at various touchpoints of the economy, and my assessment is that almost everyone is running with first-order thinking.

Today I have really pushed myself; my brain feels like it needs one of those cooling facilities that the new-age data centres use. This promises to ruffle feathers; I am holding nothing back. Let’s get to it.

The standard response to statements about the destruction of jobs and mass unemployment is to simply reflect back on history and the periods of massive productivity gains through innovation. These people say humans are infinitely creative and resourceful and will therefore discover or create new fields of endeavour that will become sources of future economic prosperity. Think here of steam engines, railroads, cars, electricity, technology, computers …

I want to dismiss this group as simplistic, but we will come back to this, as often there is brilliance within simplicity; it just requires looking in the right places.

Another group is the one I thought I was in. It turns out that I have one foot in this camp and one in a new group that requires second-order thinking as an entry requirement. Here I am referring to the thesis that AI and the robots that accompany it will take over most of society’s jobs. Dario Amodei, the CEO of Anthropic, believes we will soon be at 50% unemployment. Musk believes that we will be closer to 100%, and jobs will be hobbies only. With this the winners will be the companies that own the AI and robots that are responsible for the jobs, and they will make super profits. Most companies that are employing thousands of employees will no longer stay in business. The explosion in productivity will drive down costs, and governments will be forced to provide a universal basic income (UBI) from the taxes on the super profits the AI and robotic companies make.

If you have been paying attention, the obvious question is where will the money come from to pay the AI and robotics companies for their services?

To answer this question we first need a basic lesson in macroeconomics. Do not be scared of this formula; it is not that complicated. The GDP equation is these few letters:

GDP = C+I+G+(X−M)

If C (consumption) falls due to job loss, the system must offset via:

I — massive AI capex

G — government redistribution/spending

X — exports

M — imports

Stay with me here; this is important. GDP will contract despite productivity gains simply because the customers will increasingly be paying for the AI services from their UBI, which will be enough to sustain society as the cost of goods and services drops to a level of sustainability. This is what I called the subject of today’s letter, The Abundance Recession.

In a way this is what John Maynard Keynes had in mind when he wrote his 1930 essay “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren”. In his essay he predicted:

Massive productivity gains

Falling labour demand

A future of abundance

But he warned of “technological unemployment", where he foresaw labour displaced faster than new uses emerge. This is exactly what we are staring down today. Keynes was not early; he was wrong. Keynes’ concern wasn’t production. It was aggregate demand. I fear if I go too deep into the mechanics of aggregate demand, I will lose many of you, and in my mind, it is a detail that is surplus to requirements for this letter. Stay with me. I have not introduced my thesis yet.

Back to Keynes, he believed that if machines produce and workers earn less, consumption falls. He assumed leisure would fill the gap. I believe that this point is where Keynes is likely to be wrong again.

Up until this week I think I had fallen in love with the happy-ending utopian ideal that Keynes had envisaged and was repressing Karl Marx’s views on Capital being the ultimate source of class wars and society’s collapse. It turns out that I think some of what Marx had in mind is likely to be closer to the truth than we care to admit. I say that as a card-carrying capitalist and anti-communist, but a dyed-in-the-wool realist. Inequality is off the charts and the protest movement is at a boiling point.

In order for me to make my case, I want to share a thought experiment that sits outside economics but has profound implications for how we think about the economy that is emerging.

In 1974 the American philosopher Robert Nozick published a book titled Anarchy, State and Utopia. It was not written about technology, markets, or artificial intelligence. It was written as a challenge to utilitarian philosophy and to the idea that maximising happiness is the ultimate objective of society. But buried inside that work is a question that feels almost prophetic in the context of the AI age. At least to me and that is why I thought of it.

Nozick asked readers to imagine a machine that could simulate any experience they desired. You could plug in and live a life of achievement, love, recognition, success, and happiness. The experiences would feel completely real. You would not know you were inside a simulation. From the inside, your life would feel rich, meaningful, and fulfilled.

Yet none of it would actually be happening in the external world.

Nozick then asked the simple but devastating question. If such a machine existed, would you choose to plug in permanently?

Anyone getting Matrix vibes?

Most people instinctively recoil at the idea. And the reason they do is revealing. It is not because the machine fails to deliver pleasure. It is because we value authenticity. We value doing things, not just experiencing the sensation of doing them. We value being a certain kind of person, not just feeling like one. We value contact with reality, even if that reality is imperfect.

With all of the above as an introduction, let me get to my point about how I see things in fact playing out in the near future.

I want to begin by saying that I do not reject the UBI argument outright. In fact, I think there is a very high probability that some form of redistribution emerges, whether we call it UBI or not. The productivity gains from AI and robotics are simply too large and too concentrated to avoid political intervention. Governments will tax the supernormal profits of the firms that own the intelligence layer, and some portion of that will be recycled back into society to maintain social stability and baseline consumption. Combined with the massive deflation in the cost of goods and services that AI will drive, people will feel that they can survive financially even if traditional employment opportunities shrink. Survival itself becomes cheaper.

But survival is not the same as meaning, and it is certainly not the same as trust.

This is where I want to bring in Nozick’s thought experiment, not as philosophy for its own sake, but as a lens through which to view the emerging economy. If we would not willingly plug into an experience machine, even one that guarantees happiness, then we are admitting something fundamental about human nature. We value authenticity. We value contact with reality. We want to know that what we are seeing, reading, hearing, and feeling has a lineage, a source, and a truth attached to it.

I already feel this tension in my own consumption habits. I struggle to read a newsletter or a social media thread that is obviously fully generated by AI. It is not that the information is wrong. Often it is technically perfect. But it feels hollow. There is no lived experience behind it, no scars, no intellectual lineage, no personal risk taken in forming the view. It is information without a human signature. And I find myself disengaging from it instinctively.

Now scale that discomfort from newsletters to the entire information ecosystem.

As the technology becomes more powerful, the incentives for its misuse expand exponentially. Every tool that allows a corporation to optimise productivity also allows a criminal to optimise deception. Voice cloning enables customer service efficiency and fraud simultaneously. Synthetic media enables marketing and political destabilisation simultaneously. Autonomous agents enable workflow automation and cyber intrusion simultaneously.

We do not live in a world populated only by benevolent actors. We live in a world that includes crooks, psychopaths, hostile states, ideological extremists, and opportunists of every variety. To assume that the most powerful technological stack ever created will be used exclusively for productive purposes is historically naive.

Human history suggests the opposite. Every technological leap expands both civilisation and its shadow.

This is where I believe the current unemployment forecasts from people like Musk or even Amodei may be missing a critical second order offset. They are looking at labour purely through the lens of production. They see factories automated, code generated, legal work processed, and conclude that human labour becomes redundant.

But they are not fully pricing the labour required to defend society from the misuse of that same intelligence layer.

If reality itself becomes contestable, verification becomes labour intensive. If identity becomes forgeable, authentication becomes labour intensive. If financial systems become infiltratable, surveillance becomes labour intensive. If autonomous agents can exploit systems, counter agents must be deployed to monitor, audit, and neutralise them.

In Schumpeterian language, we may still get creative destruction, but the creation phase may not sit where we expect. It may not be in new consumer industries or leisure sectors. It may sit in security, verification, compliance, cyber defence, infrastructure resilience, narrative intelligence, and system policing. Entire employment classes built not to produce output, but to protect the integrity of output.

In that world, the labour market does not disappear. It mutates.

We move from an economy organised around production to one organised around protection.

The paradox is that people may feel financially able to survive due to deflation and redistribution, yet societally anxious because trust is continuously under assault. Jobs exist, but many of them are defensive in nature. GDP optics weaken because automation suppresses measured output, yet employment holds up because the threat layer requires constant human oversight.

We end up in an equilibrium that is economically functional but psychologically adversarial. A society where abundance is real, employment is real, but reality itself is permanently questioned.

If we borrow the metaphor from The Matrix, we can think about the AI transition as a civilisational pill choice. The red pill is the comforting vision many economists and technologists are gravitating toward. A world of abundance, leisure, and post-scarcity living. Machines produce, humans relax, and society drifts into a Keynesian utopia where work becomes optional and meaning is self-directed.

The blue pill is less comforting. It is a world where intelligence is abundant but trust is scarce. Where survival is affordable but reality is contested. Where employment exists not because we need more production but because we need more verification, more policing, more defence against the misuse of the very systems we built. It is sustainable, but it is adversarial.

The red pill is elegant as a thought experiment. It is clean, frictionless, and detached from the behavioural realities of human nature. The blue pill is messier. It accounts for deception, power, conflict, and the darker gradients of technological misuse.

If I am honest about the direction of travel, I struggle to see us choosing the red pill path. We are already building authentication layers, surveillance systems, cyber defence units, and verification economies faster than we are building leisure infrastructures.

In many ways, society may already have swallowed the blue pill without fully realising it.

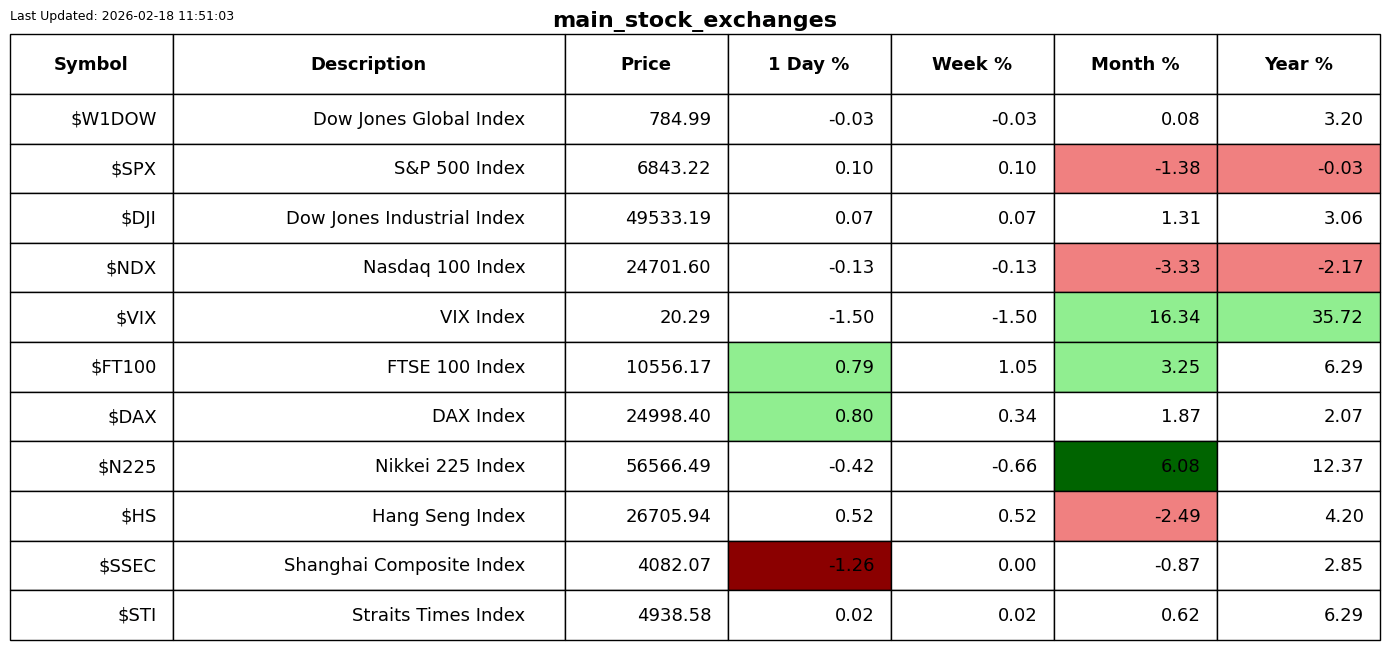

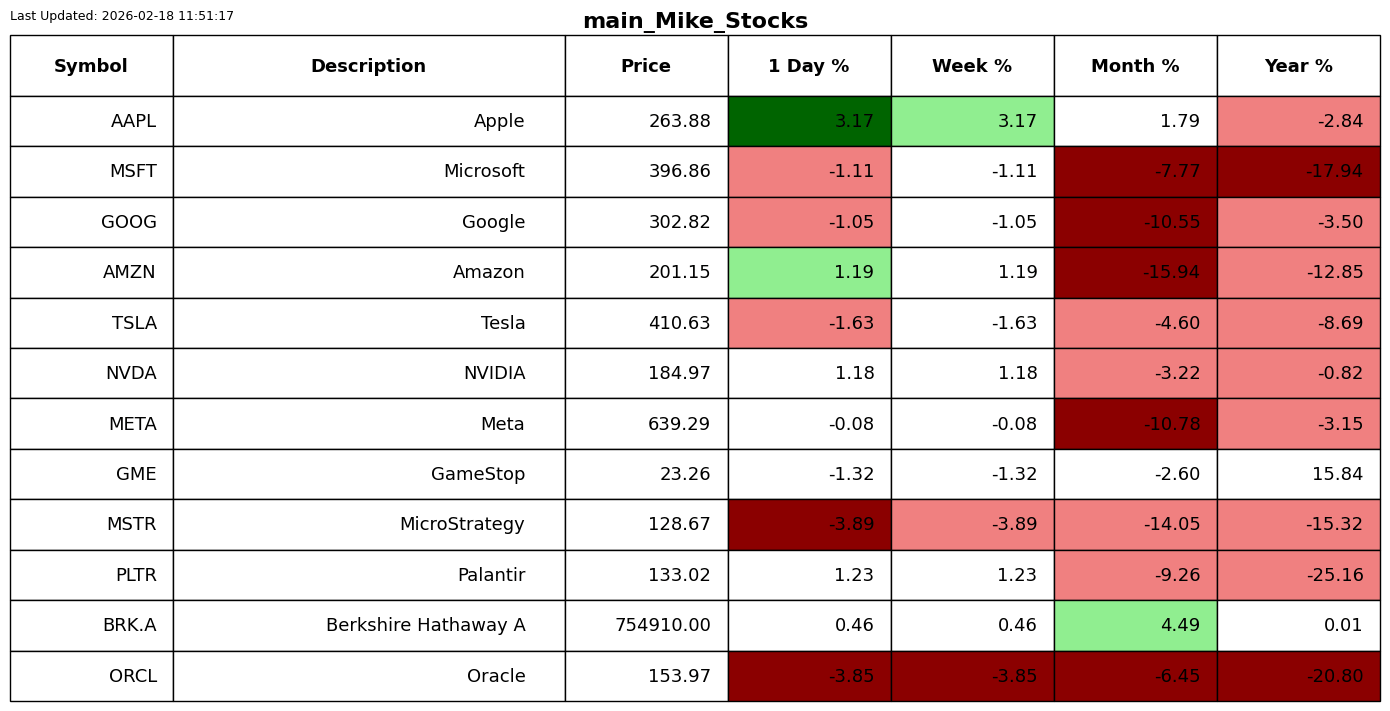

S2N Observations

That is what going viral looks like. Peter Steinberger went from Clawdbot founder to head of agentic work at OpenAI quicker than my antivirus can update. If this is new to you, then you can catch up here.

S2N Screener Alert

I am skipping alerts today.

Brought to you by S2N Navigator, a professional AI-integrated research and performance analysis platform for traders who care about truth. It connects backtests, live trades, and portfolio data into a single workflow that highlights bias, overfitting, and fragile strategies before they cost real money.

If someone forwarded you this email, you can subscribe for free.

Please forward it to friends if you think they will enjoy it. Thank you.

S2N Performance Review

S2N Chart Gallery

S2N News Today

. Let's